John Hoyland: Blood on the canvas, by a modern master

John Hoyland has been called Europe’s answer to Mark Rothko. On a visit to his London studio, esther walker discovers why the celebrated painter has turned to Robert Fisk of The Independent for inspiration in his latest artworks.

The Independent, April 25, 2008

“I borrow anything from anything,” says the artist John Hoyland. “I’ll borrow from other people’s work, nature, flowers – anything.” In his latest exhibition, Greetings of Love, Hoyland borrows from a more unlikely source, perhaps: a photograph of blood-spatter on the floor of a hospital in Lebanon, accompanied by a piece, about the 33-day conflict in Lebanon and northern Israel in 2006, by The Independent’s Robert Fisk.

John Hoyland in his studio. Photo: Teri Pengilley

“I’ve always liked Robert Fisk’s writing and I admire him. I thought the piece that he had written was rather moving, and I looked at the photograph that went with it and it looked just like one of my paintings.” The piece, published in August 2007, was a reflection on the previous year’s war in Lebanon and, in part, a review of the book Double Blind by the Italian photographer Paolo Pellegrin.

Love and loss: ‘Lebanon’ by John Hoyland

Pellegrin’s picture, taken in Tyre’s main hospital, shows a large splash of blood on the black-and-white tiled floor of a hospital; the victim had been badly injured in an Israeli rocket attack on 6 August, 2006.

“I hate wars,” reads Fisk’s piece. “I was thinking this over as I pawed through Double Blind, from which these photographs are taken. Its terrible, rage-filled, blood-spattered pages are an awful memory to me of last year’s war in Lebanon. It began on my birthday – my 60th birthday – when a dear friend called me up and told me what a terrible birthday I was going to have, and I asked why, and she told me that two Israeli soldiers had been captured by the Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and I asked Abed, my driver, to head south, because I knew that the Israelis would bomb across Lebanon. And I was right.”

Love and loss, Photo: Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum

The resulting work by Hoyland is a powerful, richly coloured image, with the artist’s trademark layers of thick paint, rivers of colour running down the canvas, and his nerve-cell-like central focus. But Hoyland insists that the piece is not deliberately political.

“I don’t see Lebanon as a political piece, although the title would indicate that. I was simply struck by the constant threat to people living in the Middle East and the sheer horror of the things that happen. I suppose my sympathies would always be with the victims and the underdog, so I suppose in that way it is political.”

Lebanon is part of a wider exhibition inspired by loss. Both Patrick Caulfield and Piero Dorazio, both artists and close friends of Hoyland’s, died in 2005 and Greetings of Love is, in part, a farewell. He has referred to the paintings for Dorazio, Poem for Piero, and Caulfield, Souvenir for Patrick, as “letters to friends” and “elegies”.

Work by artist John Hoyland

“I spend a lot of time looking for structures and looking for things to hang a painting on,” says Hoyland. “You’ve got to have a structure otherwise you’ll just paint chaos. But at the moment I’m in this thing where I’m not painting sexy or structured pictures, I’m just surprising myself with what comes out. And I’ve done a lot of paintings recently that, without thinking about it, turn out to be about loss.”

Hoyland, now 73, is regarded as the leading abstract artist of his generation, and is sometimes referred to as Europe’s answer to Mark Rothko. “I don’t think he would have liked that comparison,” says Hoyland, laughing. “I knew him a little bit and he didn’t really like other people following him at all.”

John Hoyland’s studio, Photo: Teri Pengilley

Hoyland is part of a band of post-war “Mod Brit” artists such Albert Irvin, Alan Davie and Bridget Riley who , after briefly falling out of fashion, have enjoyed a recent return to popularity. Last year Davie sold a work for £234,000, and Hoyland’s bright creations have been selling for £50,000 each. ……… V

C War and conflict are a subject close to Hoyland’s heart. National Service was scrapped the year that Hoyland was due to be called up. “I was lucky that I never had to confront that. I would never have gone into the forces if I had been called up, even though some of my contemporaries seem to have enjoyed it. And the whole purpose of becoming an artist is to be an individual; the idea of going somewhere and being given a number and doing everything you’re told doesn’t appeal to me. I just don’t go in for all this shooting people who you don’t know; it sounds crazy to me.”

John Hoyland’s studio. Photo: Teri Pengilley

The war in Iraq, Hoyland feels, was similarly inexplicable. “I’ve always been 150 per cent against the war, the folly of it and the lack of wisdom on behalf of our leaders. I mean, they might be smart people but they’ve got no wisdom. They’re just like smart lawyers. But I’m older than them so maybe that makes a difference.”

Hoyland was born in Sheffield in 1934 and attended the Sheffield School of Art and then came down to London to study at the Royal Academy school of art in 1957. As a child, he constantly drew and made things. “I just had a sort of craving to make something. I don’t know why.” His parents were supportive of him going to art school and his mother always encouraged him to draw. “She would say: ‘Oh, let him draw, he’s in the mood.’ It was also a way of getting to stay up late.”

Photo: Teri Pengilley

The Royal Academy, although prestigious, was something of a disappointment. “In the Sixties we were just taught in the old manner of drawing from the figure, and painting landscapes, still lifes – things like that. I did it and I did it reasonably well, but I didn’t have a flair for it. It was all about learning to draw in a Renaissance manner. I was always better when I picked up a brush and a palette knife. We really weren’t taught much at all, it was very dry. And when we were taught history of art it was all a bit pointless. If you hadn’t seen any of the stuff, mostly in other countries, what was the point? I’ve always thought that history ought to be taught backwards – start with today and then go back.”

He then taught at the Chelsea School of Art, where he met Caulfield, who became one of his closest friends, and then at the Slade and Royal Academy art schools. He continued to paint, exhibiting in a variety of one-man shows at the Whitechapel Gallery, the Marlborough New London Gallery and, annually, at the Waddington Galleries.

It was Hoyland’s meeting with the artist, architect and pioneer of abstract art in Britain, Victor Pasmore, that accelerated his creative progression. “I was very lucky to meet Victor on a course. All the ideas I’d been reaching towards but I had no intellectual grasp of – those were all clarified on the course. Victor sat me down one day and explained in about half an hour the difference between perspective and other kinds of space, and ideas on visual perception, and that helped me a lot – ways of rendering space without perspective. That helped me no end. I was stuck painting in Formalism, although I didn’t know it was called that at the time.”

Hoyland moved to New York in 1964, where the kind of abstract impressionism in which he was interested was at a more advanced stage. “Of course, at the start we couldn’t make head nor tail of this American art. It seemed far more sophisticated and passionate than the British art of the same time. The stuff was really mystifying. Looking back, what was amazing was that somehow Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell had taken two opposite things, Constructivism and Surrealism, and somehow blended the two. They made a new hybrid.”

From then on, Hoyland didn’t look back and became one of the most celebrated artists in the UK. “If I had died in 1969 I’d be a legend by now,” remarks Hoyland of his early success. “Someone once said to me that artists don’t really get better, they just change. If you’re no good to begin with you won’t be any good at the end.

“I read a piece by Kenneth Clark once who was also saying that it’s rare that artists get better as they get older. He put it down to a sort of ‘unholy rage’ you get in young men. When you’re young, you start out wanting to be a tough guy and to beat everyone up with your work – the instinct is to be dominant and aggressive. And then you get into middle age and start wanting to be an intellectual and showing people that you know all the polemics of the game and to show people that you can match anybody in that way, too. And then when you get old, you just go crazy.”

When Hoyland moved down to London from Sheffield he moved into the flat he still lives in now. It is part of an old abandoned hat-factory near Smithfield that he and 13 others, including the pop artist Allen Jones, bought in to for £120,000 between them. There is just one large room to live in, with a wall partially dividing the living space from the small sleeping space which you can just see while sitting on the low-backed brown leather sofas.

“The bed gets made twice a week: once when my girlfriend comes round and once when the cleaner comes round,” says Hoyland. “I don’t think you really need to make the bed with duvets, you just clamber back into your pit at night. I live like a kind of fairly rich student.”

Today Hoyland is wearing a red-and-white checked shirt, black trousers and black cowboy-boots. (“I always thought fashion was rubbish – I still do.”) His hair is a spiky shock of white and he wears large, tinted glasses, which keep slipping down his nose.

Attached to the flat where he lives is his studio, a once-large room-space now encroached upon by hundreds of canvases. The floor is thick with paint-spatters and everything else – chairs, books, doors, is covered in more paint. Hoyland’s canvases, which he has the luxury of buying pre-stretched these days, are laid onto the floor and he works above them. The canvases are tipped this way and that to achieve a dribbled effect and he uses an iridescent paint that, when it catches the light, gleams like metal.

“Everyone always remarks on the floor,” says Hoyland. “They all want to buy the floor and not the paintings!”

There is also a foot-high stack of catalogues detailing Hoyland’s 40-year exhibition history. It’s a back catalogue that speaks of a ferocious work ethic and a dedication to art. “There’s that ridiculous cliché, you know, ‘If you remember the Sixties then you weren’t there.’ Well, I was very much there and I remember them. We were never into drugs. I didn’t even really drink in those days – we couldn’t afford it. When I was a student I couldn’t even afford to take a girl out for a cup of coffee.

“I remember Patrick [Caulfield] going to Rome on this hair-raising drive in a souped-up Mini with Robert Fraser [the art dealer] and they went to this very smart party with princesses and so on. Well, someone passed him a cigarette and he took it, thinking that they’d given it to him because he was next to the ashtray, and stubbed it out. It was a joint, of course, and they all looked at him like, ‘Who’s this guy?’ We just had no idea. A lot of our students were doing LSD and they all turned out the same kind of paintings – sort of fuzzy things. They all thought they were highly original, of course. No, I was just trying to be respectable.

“I was always interested in serious art and serious literature and I had a wife and kid. I thought the Stones were overrated, although Mick Jagger’s a great showman. I preferred the blues, Miles Davis, or Bach and Berlioz.” The wife he refers to is Airi Karakainen, with whom he had one son; they divorced in 1968.

The modern art-scene seems to leave Hoyland cold; he is disappointed in the venal element that has crept into artistic endeavour. “The thing I miss in a lot of younger painters is the lack of passion and soulfulness. Nowadays to them it’s all about succeeding. When we went to art school we never dreamed we would make a living out of art, make a lot of money or become famous or anything. Now they’re all got their stuff set out with their [website addresses] and their business cards printed up.

“A lot of young artists now have an idea and want to illustrate it, but they do almost everything they can to avoid paint and the sensuality of painting. It’s all so concept-based – and the real killer is computer art. Some of it is all right when you first look at it, but when you look closer it becomes more vacuous. The whole thing for me is the spontaneity that happens in the process of creating something.”

Does he think people like Charles Saatchi, who make superstars out of art students overnight by buying their work for huge sums of money, are to blame? “Saatchi has his own taste and his own raison d’être,” says Hoyland carefully. “He’s taken a lot of risks, he’s bought some good stuff, but I think he’s bought a lot of junk as well. But it’s up to him what he does with his money.

Sadly, people’s success today is often based on how much they’re written about. These guys are very savvy – that whole generation that came out of Goldsmiths, they’re very savvy about the media. Damien [Hirst] is a smart guy. They reckon he’s the richest artist in the world. But I don’t think you make great art unless you paint it yourself.”

A lot has changed, says Hoyland, but some things are still the same. “Someone asked me the other day what the teachers at the Royal Academy were like when I was there. And I said: ‘Oh… just a bunch of grey-haired old fogeys who didn’t know what we were doing.’ And then I realised, well, we’ve come full circle!”

Greetings of Love is at Beaux Arts, Cork Street, London W1 (020-7437 5799) from 30 April to 31 May

****

‘You become accustomed to the smell of blood during war’

As a witness to unbearable horror during his years in the Middle East, Robert fisk has – on occasion – been lost for words. But he believes that John Hoyland’s artwork, capturing the brutality of conflict, is as eloquent as any journalist’s article

By Robert Fisk.

I was in the occupied Palestinian city of Hebron once, in 2001, and the Palestinians had lynched three supposed collaborators. And they were hanging so terribly, almost naked, on the electricity pylons out of town, that I could not write in my notebook. Instead, I drew pictures of their bodies hanging from the pylons. Young boys – Palestinian boys – were stubbing out cigarettes on their near-naked bodies and they reminded me of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, all arrows and pain and forgiveness, and so all I could do was draw. I still have the pictures. They are ridiculous, stupid, the work of a reporter who suddenly couldn’t bring himself to write the details on the page.

But I understand Hoyland’s picture, even if it is not my picture. After I saw the oil fires burning in Kuwait in 1991, an Irish artist painted Fisk’s Fires – a title I could have done without – in which she very accurately portrayed the bleached desert with the rich, thick, chocolate-tasting oil we tasted in the aftermath of the war. Sometimes, I wish these painters were with us when we saw the war with our own eyes – and which they could then see with theirs.

But John Hoyland’s Blood and Flowers quite scrupulously directs our eyesight on to the bright, glittering centre of gore that we – be we photographers or writers – look at immediately we enter the centre of that little Golgotha which we wish to visit and of which we never wish to be a part: the hospital. Blood is not essentially terrible. It is about life. But it smells. Stay in a hospital during a war and you will become accustomed to the chemical smell of blood. It is quite normal. Doctors and nurses are used to it. So am I. But when I smell it in war, it becomes an obscenity.

I remember how Condoleezza Rice, when she was Secretary of State, visited Lebanon at the height of the war – at the apogee of the casualties – and said that the birth of democracy could be bloody. Well, yes indeed. The midwifery was a fearful business. Lots of blood. Huge amid the hospitals. God spare us Ms Rice’s hospital delivery rooms…

I’m not sure how sincerely we should lock on to art to portray history (or war). I have to admit that Tolstoy’s Battle of Borodino in War and Peace tells me as much about human conflict as Anna Karenina tells me about love. I am more moved by the music of Cecil Coles – one of only two well-known British composers killed in the 1914-1918 war – than I am by Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. But this does not reduce the comprehensive, unstoppable power of great art to convince – just as a brilliantly made movie can do in the cinema.

I have to admit that I have a few worries about art and war. Can a painter who has never experienced war really understand the nature of the vile beast? Most of Britain’s First World War artists were in France, but that does not apply to Iraq. When I saw wild beasts – the desert dogs – tearing apart the corpses of men, women and children in southern Iraq (killed by the United States Air Force and, yes, by the RAF, whose pilots – God bless them – refused to go on killing the innocent) and running off across the sand with fingers and arms and legs, there was no art form to convey this horror. Film would have been a horror movie, paintings an obscenity. Maybe only photographs – undoctored – can tell you what we see.

Goya got it right. I went to see an exhibition of his sketches in Lille a few years ago – the irony of my father’s trenches a few miles away (he was a 19-year-old soldier in the third battle of the Somme) not lost on me – and was almost overwhelmed by the cruelty that he transmits. The collaborators hanging, near-naked, from the pylons seemed so close to the raped and impaled guerrilla fighters of Spain that art seemed almost pointless. What is the point of intellect when the brain will always be crushed by the body?

When the Americans entered Baghdad in April 2003, I ran into the main teaching hospital in Baghdad to find a scene of Crimean war proportions. Men holding amputated hands, soldiers screaming for their mothers as their skin burned, a man without an eye, a ribbon of bandage allowing a trail of blood to run from his empty socket. Blood overflowed my shoes. I guess it’s at times like this that we need John Hoyland.

All Souls: The Frida Kahlo cult

By Peter Schjeldahl, The New Yorker, November 5, 2007

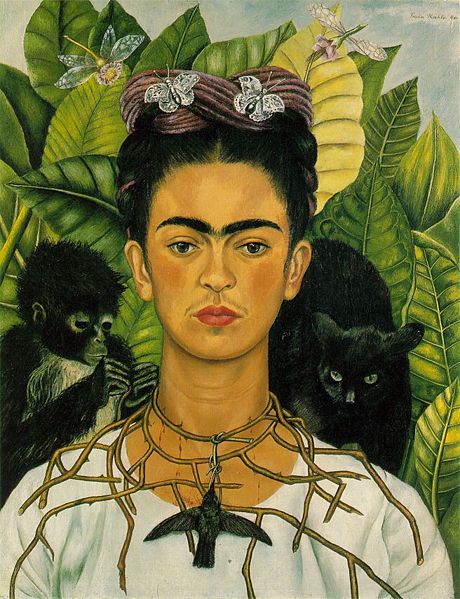

There are so many ways to be interested in Frida Kahlo, who was bor a hundred years ago and died forty-seven years later, in 1954, tha simply to look at and judge her paintings, as paintings, may seem narrow-minded. No one need appreciate art to justify being a Kahlo fan or even Kahlo cultist. (Why not? The world will have cults, and who better merit one?) In Mexico, Kahlo’s ubiquitous image has become the counter-Guadalupe, complementing the numinous Virgin as a deathless icon o Mexicanidad. Kahlo’s ascension, since the late nineteen-seventies, the feminist sainthood is ineluctable, though a mite strained. (Kahlo struggle not in common cause with women but, single-handedly, for herself.) An her pansexual charisma, shadowed by tales of ghastly physical an emotional suffering, makes her an avatar of liberty and guts. However Kahlo’s eminence wobbles unless her work holds up. A retrospective a the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, proves that it does, and the some. She made some iffy symbological pictures and a few perfectl awful ones—forgivably, given their service to her always imperille morale—but her self-portraits cannot be overpraised. They are sui generi in art while collegial with great portraiture of every age. Kahlo is amon the winnowed elect of twentieth-century painters who will never be absen for long from the mental museums of future artists.

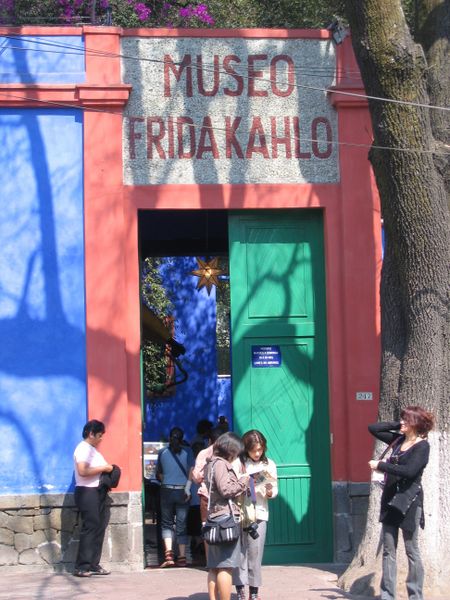

The Blue House.

She was born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón in the house where she would die, in Coyoacán, then a prosperous suburb and later a district of Mexico City. She was the third child of a Hungarian-German immigrant photographer, who was an atheist Jew, and a pious mestiza from Oaxaca. Polio, at age six, withered her right leg and foot. She was among the rare girls admitted to the sterling National Preparatory School, in Mexico City, where she grew from an effervescent tomboy into a brilliant young woman, during the creative tumult of the nineteen-twenties. When she was eighteen, a bus crash left her with spinal and pelvic damage that would entail many surgeries, some of them probably unnecessary. (Was she masochistic? Anyone doomed to a lifetime of pain will find veins of sweetness in it.) While convalescing, she began to paint, depicting herself, in styles influenced by Renaissance and Mannerist masters, with the aid of a mirror set in the canopy of her bed. In 1928, she took up with Mexico’s chief artist, Diego Rivera, who was twenty years her senior. They married in 1929, divorced for a year in 1939, then remarried. They were the loves of each others’ lives, though with innumerable supplements. Their semi-public affairs (her amours included Leon Trotsky and numerous women); their dealings with famous figures in America and Europe, from John D. Rockefeller to Pablo Picasso; and their political adventures, as Communists subject to sectarian pushes and pulls, make Hayden Herrera’s hugely consequential biography, “Frida” (1983), a delirious read. (Herrera is a co-curator, with Elizabeth Carpenter, of the Walker show.) Kahlo died, probably of a complication of pneumonia, the last in a cascade of deteriorative maladies, a year after the opening of her first solo exhibition in Mexico.

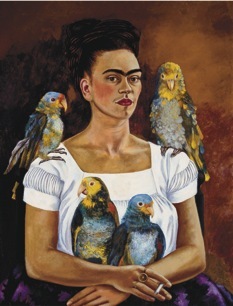

Rivera often remarked, correctly, that Kahlo was a better painter than he was. Picasso confessed himself incapable “of painting a head like those of Frida Kahlo.” André Breton praised her art—with enthusiasm marked by condescension—as “a ribbon around a bomb.” In point of fact, the ribbons and other feminine adornments that she renders are, themselves, rhetorically explosive. Breton also claimed her as an exemplar of international Surrealism. Wrong again. At her best, she is a better artist than any of the Surrealists except Salvador Dali at his best, unless early Giorgio de Chirico may be deemed Surrealist before the letter. Besides, the avant-garde most germane to Kahlo’s development in the twenties is that of German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), which mined heightened realism for psychological drama. To this, she added fecund inspirations from Mexican pre-Columbian and folk art and Spanish-colonial and Creole portraiture. No swoons into the supposed unconscious—even most of her dream pictures are wide awake. She was terrific at still-lifes of fruit and flowers and at picturing animals—she intermittently maintained a menagerie of dogs, cats, parrots, and monkeys—all of which channel her consciousness. Kahlo’s self-portraits are about her gaze, as subject matter, technique, and content. They dramatize sheer attentiveness. They tell us exactly what it’s like to be Frida Kahlo, with, I believe, a superbly indifferent confidence that we will not understand. She confides, but she won’t plead. She makes eye contact not with the viewer but with herself—watching herself watch herself, in an extended but closed loop. T. S. Eliot articulated the truth, regarding all successful art, of a dissociation of “the man who suffers and the mind which creates.” Make the man a woman, and Kahlo becomes singular for having engaged both parties at once—and only them. Looking at the pictures, you’re not there.

The meaning of Kahlo’s art comes across in reproductions, but not its full dynamic, which involves brooding subtleties of surface and color. The reproduced images are shiny and bright. The paintings are matte and grayish, drinking and withholding light. (Their display calls for intense illumination—that of the Mexican sun, say. They should not be hung on white walls, as they are at the Walker, where the contrast makes them look like holes in a snowbank.) The lovely, highly varied, blushing colors (even Kahlo’s browns and greens blush) don’t radiate. Fused with represented flesh, foliage, fabrics, and, yes, ribbons and jewelry, they turn their backs to us. The payoff of this reticence is an absorption in the artist’s touch. It’s easy to fantasize that Kahlo’s brushes were fingertips, able to mold her own more than familiar features in the dark. The tactility of certain self-portraits is, among other things, staggeringly sexy. In “Me and My Parrots” (1941), it combines with sharp tonal contrasts of warm color to convey invisible moistness, as of a summertime, full-body, delicate sweat. Elsewhere, the felt oneness of sight and touch stirs harrowing empathy, as in “The Broken Column” (1944). Kahlo’s nude body is split open to reveal a crumbling pillar, nails penetrating her flesh everywhere. Tears flow from her eyes, but her face is dispassionate, as always. Her pain is not her. It just won’t let her mind stray to anything else, for the moment. The work belongs to a category of images with which Kahlo confronted and endured episodes of agony, including heartbreak and rage. (Most piercing are laments of her disastrous pregnancies; she longed for children but physically could not bring a baby to term.) They aren’t great art, but they are moving testaments of a great artist.

Blisteringly scornful of self-importance—in a letter from Paris, in English, she lauded Marcel Duchamp as “the only one who has his feet on the earth, among all this bunch of coocoo lunatic sons of bitches of the surrealists”—Kahlo would surely raise her prodigious eyebrow to behold what has been made of her. But immortal fame rarely meshes with the temperament of those it befalls. It is about the wishes of others. In Kahlo’s case, the ways that she has been used by feminists, multiculturalists, bisexualists, and whatnot are readily defensible. Each catches the glint from one of her facets. Most of all, Kahlo is authentically a national treasure of Mexico, a country that her work expresses not merely as a culture but as a complete civilization, with profound roots in several pasts and with proper styles of modernity. She didn’t accomplish this by trying to, as Rivera did. She simply did it. For confirmation, visit her house, the Casa Azul, in Coyoacán, whose contents and décor are as vibrant with her presence as if she had just stepped outside. I should disclose that I’m nearly a Kahlo cultist, myself. Much that is hurt and disappointed in me feels momentarily allayed, and almost healed, when I am in the spell of her art. Like the serene Madonnas of Giovanni Bellini, with their hints of the coming Crucifixion, her self-portraits assure me of two things: first, that things are worse than I know, and, second, that they’re all right.

Further Resources:

The Official Frida Kahlo Website

The Heart of Frida exhibition in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico showcasing recently discovered letters and artwork.

The Body in Pain

Fernando Botero’s work in response to Abu Ghraib photographs.

By ARTHUR C. DANTO, The Nation, November 27, 2006 issue

Colombian artist Fernando Botero is famous for his depictions of blimpy figures that verge on the ludicrous. New Yorkers may recall the outdoor display of Botero’s bronze figures, many of them nude, in the central islands of Park Avenue in 1993. Their bodily proportions insured that their nakedness aroused little in the way of public indignation. They were about as sexy as the Macy’s balloons, and their seemingly inflated blandness lent them the cheerful and benign look one associates with upscale folk art. The sculptures were a shade less ingratiating, a shade more dangerous than one of Walt Disney’s creations, but in no way serious enough to call for critical scrutiny. Though transparently modern, Botero’s style is admired mainly by those outside the art world. Inside the art world, critic Rosalind Krauss spoke for many of us when she dismissed Botero as “pathetic.”

When it was announced not long ago that Botero had made a series of paintings and drawings inspired by the notorious photographs showing Iraqi captives, naked, degraded, tortured and humiliated by American soldiers at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison, it was easy to feel skeptical–wouldn’t Botero’s signature style humorize and cheapen this horror? And it was hard to imagine that paintings by anyone could convey the horrors of Abu Ghraib as well as–much less better than–the photographs themselves. These ghastly images of violence and humiliation, circulated on the Internet, on television and in newspapers throughout the world, were hardly in need of artistic amplification. And if any artist was to re-enact this theater of cruelty, Botero did not seem cut out for the job.

As it turns out, his images of torture, now on view at the Marlborough Gallery in midtown Manhattan and compiled in the book Botero Abu Ghraib, are masterpieces of what I have called disturbatory art–art whose point and purpose is to make vivid and objective our most frightening subjective thoughts. Botero’s astonishing works make us realize this: We knew that Abu Ghraib’s prisoners were suffering, but we did not feel that suffering as ours. When the photographs were released, the moral indignation of the West was focused on the grinning soldiers, for whom this appalling spectacle was a form of entertainment. But the photographs did not bring us closer to the agonies of the victims.

Botero’s images, by contrast, establish a visceral sense of identification with the victims, whose suffering we are compelled to internalize and make vicariously our own. As Botero once remarked: “A painter can do things a photographer can’t do, because a painter can make the invisible visible.” What is invisible is the felt anguish of humiliation, and of pain. Photographs can only show what is visible; what Susan Sontag memorably called the “pain of others” lies outside their reach. But it can be conveyed in painting, as Botero’s Abu Ghraib series reminds us, for the limits of photography are not the limits of art. The mystery of painting, almost forgotten since the Counter-Reformation, lies in its power to generate a kind of illusion that has less to do with pictorial perception than it does with feeling.

The Catholic Church understood this well when, in the final session of the 1563 Council of Trent, it decided to use visual art as a weapon in its battle with the Reformation. One of the pillars of the Reformation’s agenda was its iconoclasm–its opposition to the use of religious imagery, over which the church enjoyed a virtual monopoly. The Reformation feared that images themselves would be worshiped, which was idolatry. The Catholic response was to harness the power of images in the service of faith. Artists were instructed to create images of clarity, simplicity, intelligibility and realism that would serve as an emotional stimulus to piety. As the great art historian Rudolph Wittkower observed:

Many of the stories of Christ and the saints deal with martyrdom, brutality, and horror and in contrast to Renaissance idealization, an unveiled display of truth was now deemed essential; even Christ must be shown “afflicted, bleeding, spat upon, with his skin torn, wounded, deformed, pale, and unsightly,” if the subject requires it. It is these “correct” images that are meant to appeal to the emotions of the faithful and support or even transcend the spoken word.

It took more than twenty years for artists to devise a style that executed these directives, and there can be little doubt that the art of the Baroque was successful in its mission. The art achieved extraordinary precision in the depiction of suffering and hence in the arousal of sympathetic identification. It is often noted that we live in an image-rich culture, and so we do. But most of the images we see are photographs, and their effect can be dulling, if not desensitizing. To elicit the kinds of feelings at which the Counter-Reformation aimed, photographs now often need to be enhanced. Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ is not realistic in the sense in which photography is realistic: It is enhanced and amplified, showing Jesus “afflicted, bleeding, spat upon, with his skin torn, wounded, deformed, pale and unsightly,” in a manner that would have pleased the Council of Trent. Sontag was right: Photography must be augmented–with text, she proposed–if we are to feel the pain it shows. A picture may be worth a thousand words, as the cliché goes, but a photograph does not speak for itself. At the least it requires the skilled augmentations of Photoshop–at which point, of course, visual truth is sacrificed on the altar of feeling.

The Abu Ghraib photographs are essentially snapshots, larky postcards of soldiers enjoying their power, as their implied message–“Having a wonderful time…. Wish you were here”–attests. The nude, bound bodies of the prisoners are heaped up like the bodies of tigers in Victorian photographs of smiling viceroys displaying the day’s hunt. There must be a quantitative impulse in the expression of gloating–think of the strings of fish held up in snapshots taken after fishing trips, yellowing on the walls of seafood stores. In another artistic response to Abu Ghraib, British painter Gerald Laing lifted the backdrop of Grant Wood’s American Gothic but replaced the two farmers with the American MPs Lynndie England and Charles Graner, signaling thumbs-up with their blue-rubber-gloved hands above a pile of bare-bottomed bodies. The Americans are in bright poster colors, while the bodies are gray and evidently cut from a newspaper photograph, reproduced with the dots of a coarse Benday screen. It is witty and a bit sickening, but it does not call up the feelings of a Baroque evocation of martyrdom.

Or, for that matter, of Botero’s Abu Ghraib series, which draws on his knowledge of the graphic, even lurid paintings of Christ’s martyrdom by Latin American Baroque artists, in which Jesus bleeds from the crown of thorns, or from the wounds left by lance points in his ravaged chest. Abu Ghraib, in Botero’s rendering, also evokes Baroque prisons, like those one sees in the paintings titled Roman Charity, where a visiting daughter breast-feeds her chained father in the gloomy light of his cell. Although the prisoners are painted in his signature style, his much-maligned mannerism intensifies our engagement with the pictures. This is partly because the prisoners’ heavy flesh–broken and bleeding from beatings–looks all the more vulnerable to the pain inflicted. While their faces are largely covered with hoods, blindfolds and women’s underpants, their mouths are twisted into expressions of pain or agony. Their arms and sometimes their legs are bound with thick rope, and sometimes a figure is suspended by his leg, or tethered by all four limbs to the criss-cross of bars that form a cell wall. Everyone is nude, except when wearing female underwear, which the Americans evidently considered the supreme form of humiliation. In some paintings, a prisoner is sprayed with urine by a guard who lies outside the frame. Broomsticks protrude from bleeding anuses; hooded men lie in their feces. Several of the paintings feature savage dogs that look like demons in medieval scenes of hell.

None of these works are for sale–Botero has said he has no interest in profiting from them. He has offered them as a collection to a number of American museums, but none have been willing to accept them, I dare say for the same reason that the Marlborough Gallery, when I visited the show, had someone searching bags and backpacks–not a common sight in commercial galleries.

Botero rather ingenuously suggested that, just as few would remember Guernica were it not for Picasso’s painting, Abu Ghraib might be forgotten if he did not make this series. But Abu Ghraib was a world event, rather than an incidental horror of war like Guernica. Yet unlike Picasso’s painting, a Cubist work that can serve a purely decorative function if one is unaware of its meaning, Botero’s Abu Ghraib series immerses us in the experience of suffering. The pain of others has seldom felt so close, or so shaming to its perpetrators.

Further resources: Read an interview with Botero about his Abu Ghraib series.

Documentary on Botero: click to watch.

Click for gallery of Botero’s work.

Watch Botero’s short movie about Abu Ghraib series: A Permanent Accusation